- Luật

- Hỏi đáp

- Văn bản pháp luật

- Luật Giao Thông Đường Bộ

- Luật Hôn Nhân gia đình

- Luật Hành Chính,khiếu nại tố cáo

- Luật xây dựng

- Luật đất đai,bất động sản

- Luật lao động

- Luật kinh doanh đầu tư

- Luật thương mại

- Luật thuế

- Luật thi hành án

- Luật tố tụng dân sự

- Luật dân sự

- Luật thừa kế

- Luật hình sự

- Văn bản toà án Nghị quyết,án lệ

- Luật chứng khoán

- Video

- NGHIÊN CỨU PHÁP LUẬT

- ĐẦU TƯ CHỨNG KHOÁN

- BIẾN ĐỔI KHÍ HẬU

- Bình luận khoa học hình sự

- Dịch vụ pháp lý

- Tin tức và sự kiện

- Thư giãn

TIN TỨC

fanpage

Thống kê truy cập

- Online: 223

- Hôm nay: 198

- Tháng: 1621

- Tổng truy cập: 5245625

China as a Seller s Market

Modern China’s past success was based on exports. Its future must be based on imports.

China owes much of its current economic success to former ruler Deng Xiaoping, who famously opened up the economy to the rest of the world. His reforms transformed China into a manufacturing powerhouse, and in doing so, they turned the country’s biggest liability – a massive and impoverished population that upsets socio-economic harmony at home and constrains Chinese power abroad – into its greatest asset. China became the world’s factory because its workers could make things cheaper than workers in other countries could. The ratio of China’s exports of goods and services to its gross domestic product increased from 4.6 percent during the first year of Deng’s rule to a high of 36 percent in 2006 – long after Deng had passed away. During the same period, its GDP increased by a factor of 18.

The transformation into an export powerhouse reshaped the global economy. China made so many goods so proficiently that it drove prices down and gutted the manufacturing sectors of formerly competitive countries. China’s workforce simply undercut most everyone else. The economic roots of the current U.S.-China trade war, as well as of China’s massive current structural economic challenges, are born from these developments.

That, however, is China’s past. China’s export industry was arguably the most important indicator of China’s economic health and its international status from 1980 to 2006. But since 2006, the importance of China’s exports has fallen; the ratio of exports of goods and services to GDP dropped to 20 percent last year. The last time the ratio was that low, Bill Clinton was president of the United States. To understand China’s present and past means understanding China’s export strategy. China’s future, however, will be defined far more not by what it sells but by what it buys.

For much of world history, China was the most technologically advanced and economically robust civilization in the world. China believed it was the “Middle Kingdom” in part because it could credibly claim to be the center of economic gravity on Earth for millennia. When the British Empire was still in its infancy and wanted to trade with the Qing Dynasty, the British discovered much to their chagrin that they possessed nothing the Chinese were particularly interested in buying. Even as the British developed an obsession with Chinese silk, porcelain and tea, the Chinese looked down on British trinkets, preferring instead to trade for things like silver that they could buy things with at home. Britain had to become a drug-dealer to pique China’s interest, and even then, only succeeded at forcing its goods into the Chinese market at gun(boat)point.

This general self-sufficiency defined China’s behavior on the global stage. Contrast it with Japan, which has virtually no natural resources of its own. The demands of a modern, industrialized economy forced Japan to procure abroad what it didn’t have at home, moving it to create a massive maritime empire in the 20th century and culminating eventually in a disastrous military defeat at the hands of the United States. China, replete with natural resources, had no such need. But that is no longer the case. China is no longer self-sufficient. It now needs to buy things from abroad to maintain its way of life. How China manages this newfound dependence on foreign resources and goods will play a major role in Chinese behavior on the world stage in the coming decades.

An exhaustive analysis would be quite a tome, so we’ll focus on three of China’s most important imports: oil, cereals and microchips.

Oil

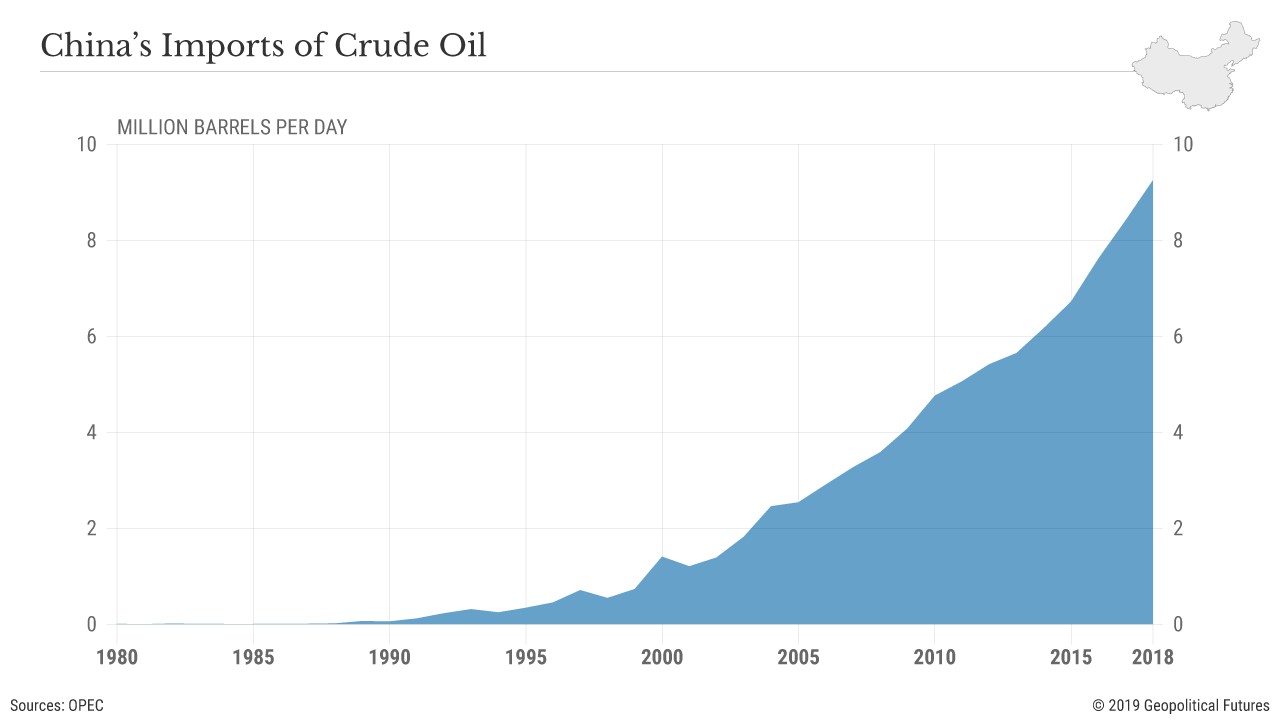

China is no longer the fastest growing oil consumer in the world – that honor now belongs to India. But China is still the largest single importer of oil in the world today – by a long shot. It imported more than 9 million barrels of oil per day in 2018, more than double India’s oil imports, and almost as much as Western Europe combined, according to OPEC. Since 1980, the amount of oil China imports has increased by a whopping 1,268 percent (not a typo).

China’s top source of oil last year was Russia, which accounted for roughly 16 percent of crude imports. China’s dependence on Russian oil could come with its own geopolitical implications depending on how far China indulges in dreams of territorial revanchism. Russia, after all, controls oil-rich Sakhalin Island only because China was forced to surrender control in the 1860 Treaty of Beijing, which ended the Second Opium War.

But the largest collective source of Chinese oil imports by far is the Middle East. In 2018, China imported over 45 percent of its oil from nine Middle Eastern countries, mostly from Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Oman, Iran and Kuwait. This means China is dependent not just on open maritime trading routes in the Middle East but increasingly on its ability to defend Chinese ships and on the political stability of a notoriously unstable region. This may force China to exert itself in the region’s political and security affairs.

Cereals: Wheat, Rice and Corn

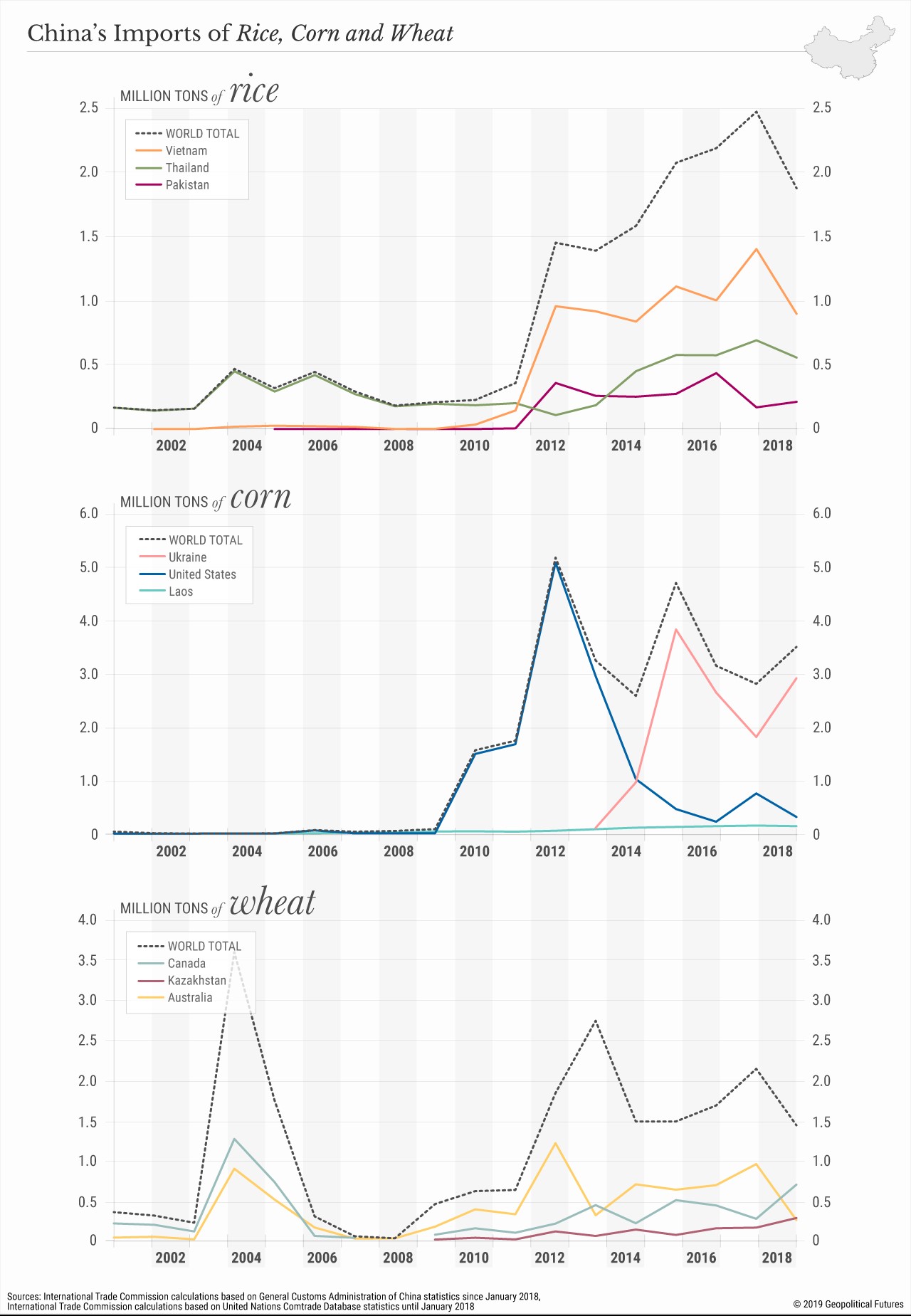

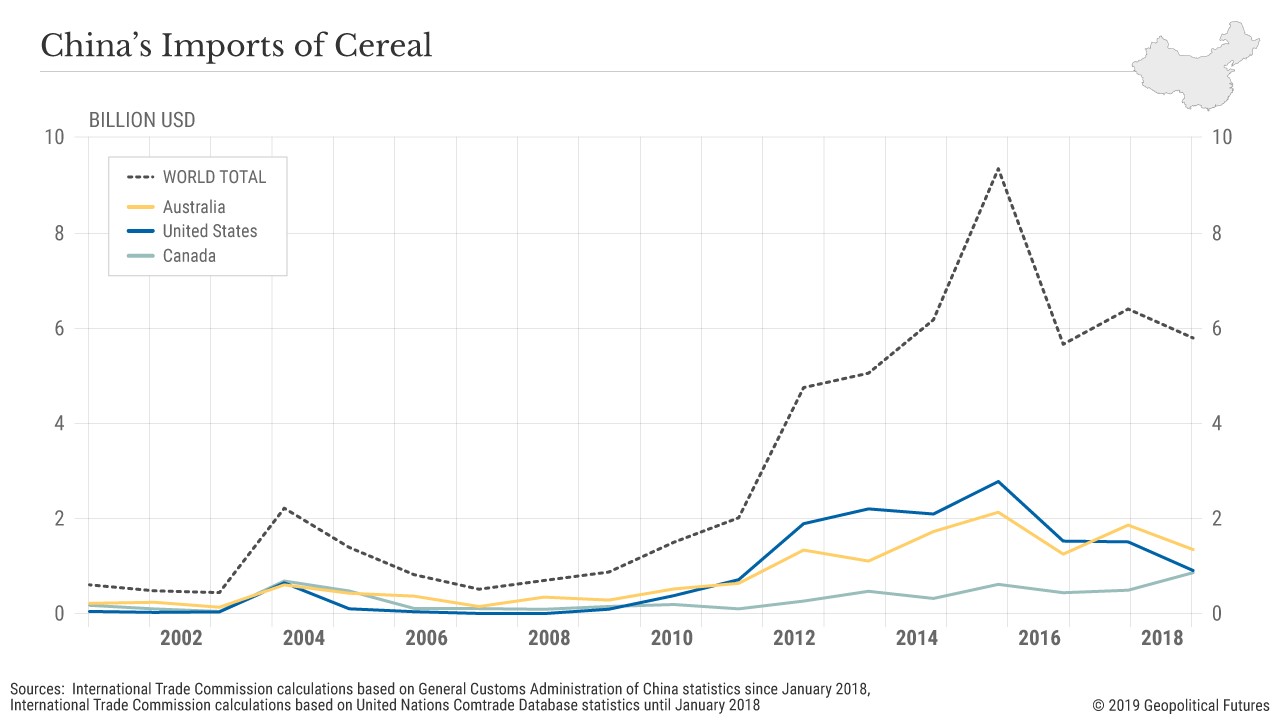

China accounts for 21 percent of the world’s population but only 9 percent of its arable land and 6 percent of its water. Yet as late as the 1950s, China was actually a net exporter of grain, particularly rice. Then it became official policy of the Communist Party to maintain grain self-sufficiency as China’s population increased. The results were tragic. From the late 1950s to the early 1960s, as many as 45 million starved to death as grain yields were exaggerated to meet Mao’s unrealistic targets.

The disaster of the “Great Leap Forward” only reinforced China’s need for grain security. Even as China became a net grain importer in 1961, importing increasingly more of it over time, China has (largely successfully) aimed to keep a 95 percent self-sufficiency rate for grain production while substantially increasing domestic grain production in the past two decades. And if the trade war is any indication, China won’t try to abandon this goal any time soon.

It’s a matter of debate whether China can continue to be self-sufficient. A recent Bloomberg report concluded that it would be impossible for China to produce enough grain for its growing population if it starts “eating like Americans.” A 2010 study by leading Chinese experts at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and China’s Rural Technology Development Center determined that not only would China be self-sufficient in grains but that technological advances and agricultural sector reforms would allow China to contribute to food security worldwide. A February 2018 article in the NPJ Science of Food Journal was less effusive but no less optimistic about the future of China’s food security, partly because China’s aging population suggests grain consumption has already entered a slow decline.

Whatever the case may be, the fact is that China has vastly increased the quantities of its cereals and grain imports – and indeed, of food in general – over the past two decades. In its report from May 2019, the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization classified China as a major importer of coarse grains, rice, oil crops, sugar, meat and dairy. Even if China manages to achieve self-sufficiency in wheat, rice and corn in the future, it will remain dependent on imports of other major crops such as soybeans and on meat. There is, after all, a difference between survival and living well – and what might pass for self-sufficiency today may no longer satisfy Chinese appetites in even 10 years.

The wealthier China gets, the more pressure its agriculture sector will be under, and the more China will look abroad for food. A recent report published by the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences and the International Food Policy Research Institute said China would achieve food security and grain self-sufficiency by 2035 – tellingly, “food security” in this context does not just mean emphasizing structural reform on the supply side of agriculture, but also, according to the report, realizing China’s Belt and Road Initiative ambitions.

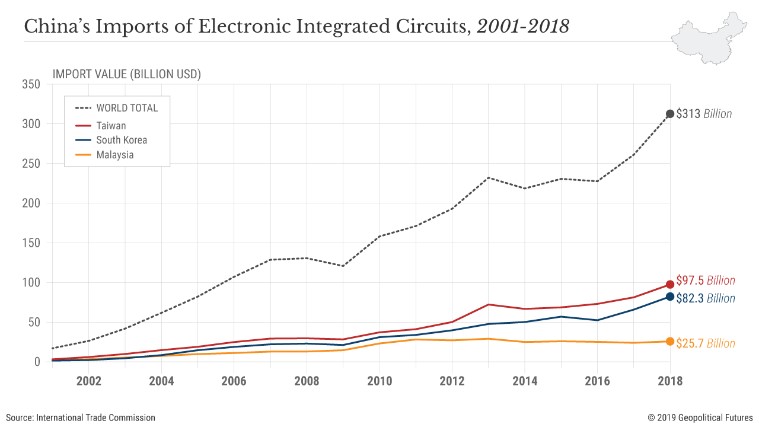

Microchips

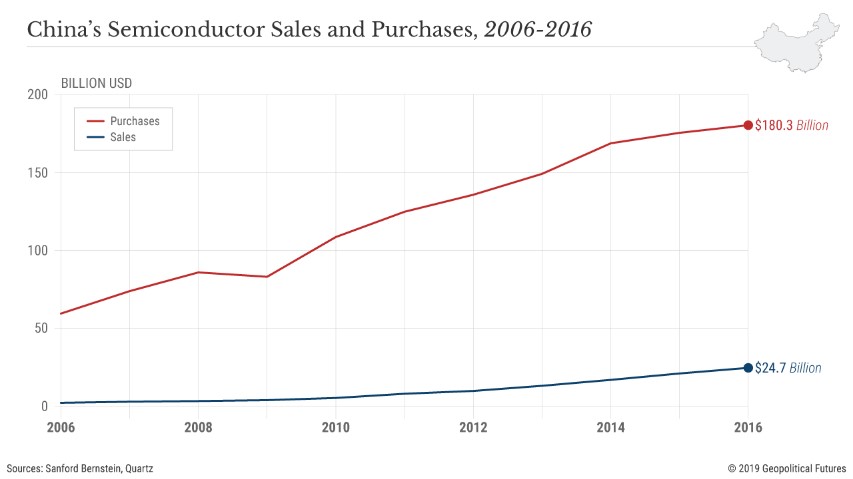

Even if the United States and China manage to reach some kind of trade deal in the coming months, their rivalry over technology will define bilateral relations for a generation to come. According to a recent study by James Lewis for the Center for Strategic and International Studies, China is the world’s largest consumer of semiconductors, accounting for 60 percent of global demand. But it produces only about 16 percent of semiconductors used domestically, and only half of these are made by Chinese firms. Beijing’s goals to increase this to 40 percent by 2020 and to 70 percent by 2025, however, will be difficult to achieve. For the time being, China will be dependent on foreign suppliers of advanced chips.

Over the past two decades, China has significantly increased its imports of electronic integrated circuits. But unlike, say, food and oil, the real value of microchips is in the technological expertise needed to produce them. China’s dependence on microchip imports will therefore manifest differently from its imports of goods and resources. China will continue to import chips with the goal of weaning itself off of any dependence on foreign technology or advanced parts. Whether and how fast China is able to do this will determine how aggressive China can be as it pursues its interests on the world stage.

Unfortunately, no single statistic exists to evaluate how quickly a country’s technological prowess is increasing. In terms of value, China’s semiconductor imports in 2018 were almost equal to the value of China’s oil imports during the same year, underscoring their importance – and China’s dependence. Data compiled by the Sanford C. Bernstein private securities firm indicated that China purchased $160 billion worth of semiconductors in 2016 while selling just $25 billion of its own. That suggests China has a long ways to go to catch up overall, but the same data also showed that China sold just $2 billion of its own semiconductors in 2006, which means Chinese semiconductor sales increased over 12 fold in a 10-year period.

The less dependent China is on foreign technology, the more aggressive China can be in securing some of its other interests and the more demanding China can be in future negotiations with other global powers.

It is hard to overstate just what a monumental transformation China has undergone since Deng first came to power in 1978. The changes have brought to Beijing’s doorstep challenges no previous Chinese dynasty has ever had to face. China may opt to mimic the U.S. approach after World War II in shaping or even creating an international system bent to China’s needs. China may take the Japanese path and attempt to secure its needs through strength. Or perhaps China will chart its own characteristically Chinese course, securing its place in the world’s globalized economy in new ways this author has not imagined. Ambiguous as the how is, that China must do so is a certainty.

By Jacob L. Shapiro

Các bài viết khác

- Bất động sản đã về dưới giá thành (22.10.2019)

- KHIẾU NẠI ĐÒI BỒI THƯỜNG ĐẤT CỦA MỘT GIA ĐÌNH CHÍNH SÁCH, TRUYỀN THỐNG CÁCH MẠNG GẦN NỬA THẾ KỶ NHƯNG CẢ HỆ THỐNG “NGÓ LƠ” – CHÍNH QUYỀN TPHCM IM LẶNG ĐỀ NGHỊ HỖ TRỢ NĂM TRIỆU ĐỒNG – CHỦ THỂ CHIẾM ĐẤT THÌ CỔ PHẦN HOÁ VÀ BÁN.. (22.10.2019)

- Thêm một dự án dân cư 50ha ở Đồng Nai bị Thanh tra Chính phủ sờ gáy (22.10.2019)

- Bất động sản ‘bất động’, nhiều ngành vạ lây (22.10.2019)

- Hàng trăm triệu người thoát nghèo, kinh tế tăng trưởng thần tốc nhưng cái giá mà Bắc Kinh phải trả quá đắt: 80% các thành phố ô nhiễm, 1,2 triệu người chết sớm vì ô nhiễm (22.10.2019)

Yahoo:

Yahoo: