- Luật

- Hỏi đáp

- Văn bản pháp luật

- Luật Giao Thông Đường Bộ

- Luật Hôn Nhân gia đình

- Luật Hành Chính,khiếu nại tố cáo

- Luật xây dựng

- Luật đất đai,bất động sản

- Luật lao động

- Luật kinh doanh đầu tư

- Luật thương mại

- Luật thuế

- Luật thi hành án

- Luật tố tụng dân sự

- Luật dân sự

- Luật thừa kế

- Luật hình sự

- Văn bản toà án Nghị quyết,án lệ

- Luật chứng khoán

- Video

- NGHIÊN CỨU PHÁP LUẬT

- ĐẦU TƯ CHỨNG KHOÁN

- BIẾN ĐỔI KHÍ HẬU

- Bình luận khoa học hình sự

- Dịch vụ pháp lý

- Tin tức và sự kiện

- Thư giãn

TIN TỨC

fanpage

Thống kê truy cập

- Online: 223

- Hôm nay: 198

- Tháng: 1621

- Tổng truy cập: 5245625

This Is Where Bad Bankers Go to Prison

Iceland's Kviabryggja Prison is an old farmhouse bound by the North Atlantic on one side and fields of snow-covered lava rock on another.

Kviabryggja Prison in western Iceland doesn’t need walls, razor wire, or guard towers to keep the convicts inside. Alone on a wind-swept cape, the old farmhouse is bound by the frigid North Atlantic on one side and fields of snow-covered lava rock on another. To the east looms Snaefellsjokull, a dormant volcano blanketed by a glacier. There’s only one road back to civilization.

This is where the world’s only bank chiefs imprisoned in connection with the 2008 financial crisis are serving their sentences. Kviabryggja is home to Sigurdur Einarsson, Kaupthing Bank’s onetime chairman, and Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson, the bank’s former chief executive officer, who were convicted of market manipulation and fraud shortly before the collapse of what was then Iceland’s No. 1 lender. They spend their days doing laundry, working out in the jailhouse gym, and browsing the Internet. They and two associates incarcerated here—Magnus Gudmundsson, the ex-CEO of Kaupthing’s Luxembourg unit, and Olafur Olafsson, the No. 2 stockholder in the bank at the time of its demise—can even take walks outside, like Kviabryggja’s 19 other inmates, all of whom were convicted of nonviolent crimes.

It may not be hard time, but it’s a far cry from the giddy days when the Kaupthing bankers hosted parties for clients aboard yachts in Monte Carlo and hired the likes of pop legend Tom Jones to serenade guests at London galas. In sentencing these financiers to serve terms of up to 5½ years, the Icelandic courts have done something authorities in the world’s two great banking capitals, New York and London, haven’t: They’ve made bankers answer for the crimes of the crash. “The Icelandic banks went overboard,” says Olafur Hauksson, the onetime small-town police chief who in January 2009 was appointed special prosecutor to investigate the banking cases. “They were basically bankrupt.”

Hauksson is still at it. In March his office indicted five others for market manipulation and fraud, including Larus Welding, former CEO of Glitnir Bank. In all, there have been 26 convictions of bankers and financiers since 2010. Welding declined to comment.

Holding its most powerful bankers accountable should have been a satisfying result for Iceland’s 333,000 residents. But a brewing scandal involving a secret share sale by the country’s biggest lender, Landsbankinn, has raised fears that the crony capitalism that marked the precrash era still lingers. The soaring popularity of an insurgent political movement called the Pirate Party, meanwhile, shows that anger continues to simmer beneath the surface of Iceland’s recovery. “The mood of society is still fairly dismal,” says Stefan Olafsson, a professor of sociology at the University of Iceland. “There is a loss of trust in politics, institutions, and parties. You could blame the nation for being ungrateful, because politicians have done some good things after the crisis. There is a contradiction.”

Iceland may be a faraway country with a population about the size of the Maldives, but it’s experiencing the same type of populist revolt that’s rocking governments across the West. In Spain the rise of the Podemos and Ciudadanospolitical movements has ended 40 years of two-party rule and prevented the formation of a government following the December general election. British voters will decide on June 23 whether to quit the European Union. And in America’s presidential contest, firebrands Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders—who favors prosecuting Wall Street bankers—won over voters fed up with the status quo.

Just a decade ago, the status quo in Iceland was very different. The country’s top three banks, having thrown off decades of fiscal discipline in a spasm of deregulation in the 2000s, tapped international debt markets like never before. Blessed with stellar credit ratings and access to the European Economic Area, the trio borrowed €14 billion ($15.7 billion) in 2005 alone, double their intake in 2004. But they only paid about 20 basis points, or 0.2 percent, over benchmark interest rates, according to the Icelandic Parliament’s Special Investigative Commission. It was an easy moneymaker. As the banks lent the funds back out at high interest rates, they raked in huge profits and recorded a whopping 19.7 percent return on equity in 2007. Flush with credit themselves, Icelandic households bought flats in London, took shopping trips to Paris, and jammed Reykjavik’s streets with Range Rovers. By 2008 the banks’ assets had swollen to 10 times the nation’s $17.5 billion economy.

Then came the fall of 2008 and paralysis in global markets. The banks lost their short-term funding and could no longer service their own debts. The krona’s value fell, making loans denominated in foreign currencies far more expensive. Kaupthing and its two rivals, Landsbanki Islands and Glitnir, defaulted on $85 billion in debt in October of that year, and households lost more than a fifth of their purchasing power. Citizens pelted the 135-year-old stone parliament building with eggs and rocks. Birna Einarsdottir, a marketing executive at Glitnir, was named that month CEO of Islandsbanki, a new lender formed from the old bank’s domestic assets after receivers took control. Sipping tea in a conference room with a view of Faxafloi Bay, she winces when asked to recall what it was like in those days. “Do you have something to give me if I do? A gin and tonic?” she says.

Einarsdottir says she and fellow staff members cried at their desks, struggling to understand how Glitnir had failed and what was next. The new CEO called an all-hands meeting in a hotel banquet room that was part strategy session, part group hug. With security guards outside the doors in case of protests, she urged her 1,000 co-workers to be patient with customers who feared they’d lost their livelihoods and their ability to obtain credit. The bank would regain trust by serving them, she told the throng. “I know it sounds like I’m speaking from a textbook,” she says, “but it was important for staff to see one year ahead. The only way to get through that time was to be optimistic.”

On a pale February afternoon, there are signs of economic renewal throughout central Reykjavik. Laugavegur, the main drag through town, is bustling with window shoppers. In the last few years, numerous boutiques, art galleries, and restaurants offering Icelandic delicacies such as smoked puffin have opened to serve the locals and tourists taking advantage of the devalued krona. On the waterfront, a five-star hotel is being built next to the Harpa Concert Hall and Conference Centre, an angular structure with a honeycombed glass facade the color of the sea. Constructed during the crash, the $235 million complex used to symbolize the nation’s hubris. Now, a tour guide tells visitors, it’s become an “icon of resurrection.”

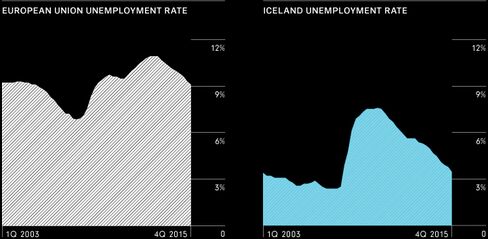

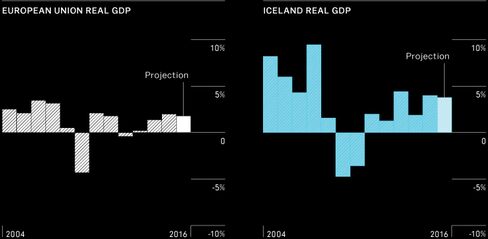

It’s a rebound other European nations would envy. Iceland’s gross domestic product is set to expand almost 4 percent this year, according to forecasts compiled by Bloomberg. The unemployment rate of 2.8 percent is about one-third the average of the European Union. As the state prepares to lift capital controls later this year, the banking sector continues to strengthen: State-owned Islandsbanki, the nation’s No. 2 lender with $8.4 billion in assets, boasts a common equity Tier 1 ratio of 28.3 percent. That’s more than twice the 12.7 percent average recorded by Europe’s 25 largest banks as of Dec. 31, according to Bloomberg data. “Before the crisis, the banks grew too fast and too much,” says Unnur Gunnarsdottir, director general of the Financial Supervisory Authority, which oversees the lenders. “That will not happen again.”

But a deal involving Iceland’s top bank and a relative of Bjarni Benediktsson, minister of finance and economic affairs, is marring this feel-good story. In November 2014, state-owned Landsbankinn sold a 31.2 percent stake in Icelandic payment processing company Borgun for 2.2 billion kronur ($18 million) in a private placement. A company controlled by Einar Sveinsson, the cabinet minister’s cousin, was part of a group that bought the shares. While there’s nothing unlawful about a private stock sale, crisis-weary Icelanders didn’t appreciate a bank—especially a state-owned one under the finance minister’s jurisdiction—executing a deal behind closed doors. Landsbankinn, which succeeded Landsbanki after it failed in 2008, has publicly disclosed similar share sales.

It didn’t help that Sveinsson’s company is domiciled in Luxembourg. Shell companies based in the secretive European duchy were a hallmark of the criminal cases Hauksson brought against the Kaupthing Four, court records show. “Why is there still such a lack of transparency about these sort of actions?” asks Birgitta Jonsdottir, a member of the Althingi, Iceland’s parliament, and co-founder of the Pirate Party. “There’s been plenty of time to fix that.”

The plot thickened last November when Visa agreed to acquire Visa Europe in a deal valued at as much as €21.2 billion. Borgun is one of 3,033 banks and payment companies that own Visa Europe. That means Sveinsson and his fellow investors are poised to more than double the value of their stake, to $12 million, when Visa completes the deal later this year, according to Landsbankinn. Outraged citizens protested in front of the lender’s headquarters in central Reykjavik in January. Someone recently hung a sign on a highway overpass: “Borgun investors: Return what you stole!”

The government’s overseer of state-owned assets is also alarmed. On March 14, Icelandic State Financial Investments, which reports to Finance Minister Benediktsson, said the Landsbankinn board should report what steps it’s taken to “regain the trust” of the public. “The sale procedure cast a significant shadow on Landsbankinn’s results and the professional appearance of the bank and its executives has been damaged,” ISFI wrote in a letter to Benediktsson. Two days later, five of Landsbankinn’s seven board members said in a statement that they won’t seek reelection at the lender’s annual shareholders’ meeting on April 14.

Landsbankinn Chairman Tryggvi Palsson didn’t return calls for comment; he said in March 2015 that the share sale was lawful but the bank should have conducted it in a public auction. Benediktsson declined to comment for this article, as did Sveinsson. The Financial Supervisory Authority also declined to comment on the affair.

The Borgun affair is unfolding as Icelanders are flocking to the Pirate Party, a left-leaning organization whose symbol is a Jolly Roger flag sporting a filleted fish instead of a skull and crossbones. The three-year-old group won the support of 38 percent of prospective voters in a March opinion poll, 2 percentage points behind the ruling Independence-Progressive coalition. If the party’s support holds, it could win 26 seats in the 63-member parliament in the next election in April 2017. Pirate Party co-founder Jonsdottir, a Doc Martens-clad writer and activist who calls herself a “poetician,” could be in a position to block government plans to eventually sell Landsbankinn and Islandsbanki. “The same parties that ran this country into the ground during the privatization from 2000 to 2004 now want to privatize the banks again,” says Jonsdottir, who sits on the legislature’s Constitutional and Supervisory Committee. “I have a massive problem with that, and it won’t happen if I have anything to do with it.”

Meanwhile, Hauksson, a bear of man with a fighter’s jaw, is pressing ahead with a half-dozen more cases related to the crash. The former top lawman in Akranes, a port town up the coast from Reykjavik, Hauksson was one of only two applicants for the job of special prosecutor—and the only lawyer. “It was important for the country to look carefully at what happened in the months that led up to the banking collapse,” he says. Few expected him to succeed in untangling the web of self-dealing that stretched from Reykjavik to Luxembourg to London. “He was used to issuing parking fines and breaking up drunken brawls,” says Sigrun Davidsdottir, a journalist who writes about the bank cases on her website, Icelog. “It’s earth-shattering what he’s accomplished.”

Working with the Financial Supervisory Authority, his office found that the country’s top three banks routinely made huge loans to their biggest stockholders. Worse, the banks secured the debts with their own equity, which spelled doom when share prices nosedived in September 2008. That month, Kaupthing Chairman Einarsson and CEO Sigurdsson surprised investors by announcing that Sheikh Mohammed bin Hamad bin Khalifa al Thani, a member of Qatar’s royal family, had acquired a 5.1 percent stake in the bank. The two bankers, with the help of Gudmundsson in Luxembourg and stockholder Olafsson, had directed Kaupthing to lend the sheik $280 million to buy the stake through a daisy chain of shell companies in the British Virgin Islands and Cyprus, according to court records. Arion Bank was formed from the domestic assets of Kaupthing after it failed in October 2008.

By misrepresenting Kaupthing’s true condition, the four men defrauded investors and manipulated the bank’s valuation, the courts ruled. In February 2015, Iceland’s Supreme Court called the actions “thoroughly planned” and “committed with concentrated intent.” The Kaupthing Four argued their actions were lawful and blamed the bank’s failure on the global financial crisis. Hauksson scoffs at that argument. “That was the reason for everything,” says the prosecutor in an office where virtually every inch of surface space is stacked with legal filings. “The verdicts stripped away their excuses.” Al Thani, who never commented publicly in the case, wasn’t charged. Contacted through prison administrators, Einarsson, Sigurdsson, Gudmundsson, and Olafsson declined to comment.

In contrast to the Icelandic saga, no bank CEOs in the U.S. or the U.K. have been convicted for their roles in the subprime mortgage crackup and related disasters. Bringing white-collar criminal cases may be easier in Iceland because courts don’t use juries. Rather, they employ neutral experts to help judges understand the intricacies of finance. In Britain’s highest-profile case stemming from the crash, the country’s Serious Fraud Office investigated London-based real estate magnates Vincent and Robert Tchenguiz in connection with their business dealings with Kaupthing. The brothers were never charged, and in 2014 the SFO even had to pay them £4.5 million ($6.4 million) in damages to settle their claims of malicious prosecution.

For its part, the U.S. Department of Justice has refrained from prosecuting individual bankers after a Brooklyn, N.Y., jury in 2009 acquitted two former hedge fund managers at Bear Stearns accused of securities fraud. “Washington wasn’t willing to take the risk of another stinging defeat, so they slowed down a host of other prosecutions,” says John Coffee, a professor of securities law at Columbia in New York.

In 2013 then-U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder told Congress that Wall Street banks are so big that prosecuting them might harm the economy. He later stressed no institution is above the law. Some watch-dogs are appalled the feds chose only to extract big civil fines from institutions. “There’s no justification over what appears to be a lack of effort to identify individuals engaged in misconduct and to bring charges,” says Phil Angelides, chairman of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, a bipartisan panel established by Congress. “It sends a signal that if you do wrong on Wall Street, there’s really no consequences. That’s bred cynicism about the justice system, and it’s bred anger.”

While Iceland’s leaders have meted out justice by jailing financiers, they still have work to do to repair the damage wrought by the crash. “The politicians did fail,” says sociology professor Olafsson. “They allowed this thing to happen, all the excesses and the greed and the debt accumulation. Something broke in terms of trust.”

Back at Kviabryggja Prison, the tumult in the capital seems worlds away. It’s dead quiet around the single-story barracks, and in the distance rise massifs that form Iceland’s western fjords. The Kaupthing convicts are marking time in different ways. A couple of them are tutoring fellow inmates. The subjects: math and economics.

Các bài viết khác

- Sau 24 năm vẫn còn thời hiệu khởi kiện? (09.05.2016)

- Obama Vows to 'Bury Last Remnants of Cold War,' Encourage Hope and Change (09.05.2016)

- Núi nợ đe dọa nền kinh tế (09.05.2016)

- Nếu biết lịch làm việc của Elon Musk, bạn sẽ không thể tin ông ấy là con người (09.05.2016)

- Muốn trở thành "Thượng Hải của Việt Nam" như lời bí thư Thăng, TPHCM cần thay đổi những gì? (P1) (09.05.2016)

Yahoo:

Yahoo: